November, 2010

On November 12th, 2010, the near-perfect Thomas Aloysius Pemberton died. One of his neighbors, Andrew, called me. Andrew and his partner Dez had seen an ambulance pull up to the house that morning. Mr. Pemberton’s cleaner found him dead in his chair. The record player was still spinning although the record had finished several hours earlier. On the turntable was Song for My Father by Horace Silver, a fine album to end on.

I believe it was a stroke he suffered or it might have been a heart attack. I’m not really sure and I don’t care. I remember when my favorite cat died. They said it was a clot or something vague like that. I didn’t understand it at the time and I still don’t. I found the reason of my cat’s death the furthest from my concerns. Unless some skullduggery is involved or there is lesson in health to be learned, the reason of someone’s death is less important information than the contents of their hard to reach cabinets above the refrigerator (which, as we all know, are only filled with Tupperware we never use and the instruction manual for a microwave…even if we don’t own a microwave). It’s funny how I compare the death of Mr. Pemberton to the death of my favorite cat. That would seem to diminish Mr. Pemberton in some way but in fact it’s quite the opposite. Nothing my cat ever did or anything about him bothered me in any way. He was great all of the time. There’s not one person I’ve ever met that made me feel that way except Mr. Pemberton.

The funeral took place at Saint Theresa’s in West Roxbury. In the church, in the row in front of me and about ten feet to my right, I noticed a couple in their late sixties or early seventies. They spoke to each other in what I thought was German. During the service, I observed their grief. It was plain to see that the husband was there to support his wife and had little to no direct connection to Mr. Pemberton. The woman clearly knew Mr. Pemberton. Her grief was unique and quite deep. It stood apart from the rest of the grief of everyone else. It was almost like this moment triggered some past painful experience.

A reception was held nearby at The Corrib. I ordered a bourbon at the bar and while I waited, I heard a crackly voice say, “You must be Chris”. I turned around there was a smiling man in his late 80’s. He had wild eyebrows that looked like dogfights, the ones that old white men often seem to have. Time had bent him over a little bit and although he probably should have been using a cane, he did not have one. His white hair went straight back with no part and he had most of it. Beneath those apocalyptic eyebrows were a set of intense darks eyes. They didn’t exactly look like Mr. Pemberton’s eyes but they shared some intangible quality I could not identify.

“My name’s Frank Rosenberg. I’m TAP’s war buddy.” Frank spoke in a way that no one longer speaks, almost like a 1940’s radio announcer.

“Yes! Mr. Pemberton told me about you! You’re the reason he came to Boston many years ago.”

I was genuinely excited to make this man’s acquaintance, so much so I was about to transfer my excitement into a vigorous handshake but stopped myself, remembering the time years ago that I had given a hearty handshake to my brother in law’s elderly father that left him with a sore shoulder for weeks. With a gentle yet respectable measure, I shook Frank’s hand.

“I’m also part of the reason he made all that money! I was his business partner. When TAP came out here, we got drunk for a few weeks and believe it or not, out of that came a solid business idea!”

“That’s great. I’m so glad to hear I’m not wasting my time when I’m drinking. I can’t believe I’m only meeting you now. Mr. Pemberton told me a lot about you and your fuel injection business. You got your inspiration for your business from the war, right?”

“You got it, slim. The first time TAP and I saw or heard of fuel injection in a motor was in some of the European airplane engines. We thought it had great potential within the American motor industry so we set up a ‘lab’, if you will, in Boston and tried to develop our own ‘brew’. We had a lot of lean years but we stuck it out and by the 80’s, some form of our patented technology was being used in almost all American automobiles.”

I was still reeling from the fact he called me “slim”. “So that means you can buy me a drink?”

Franks laughed. “It depends on what kind of drink. Anything more than Bud will require financial assistance.”

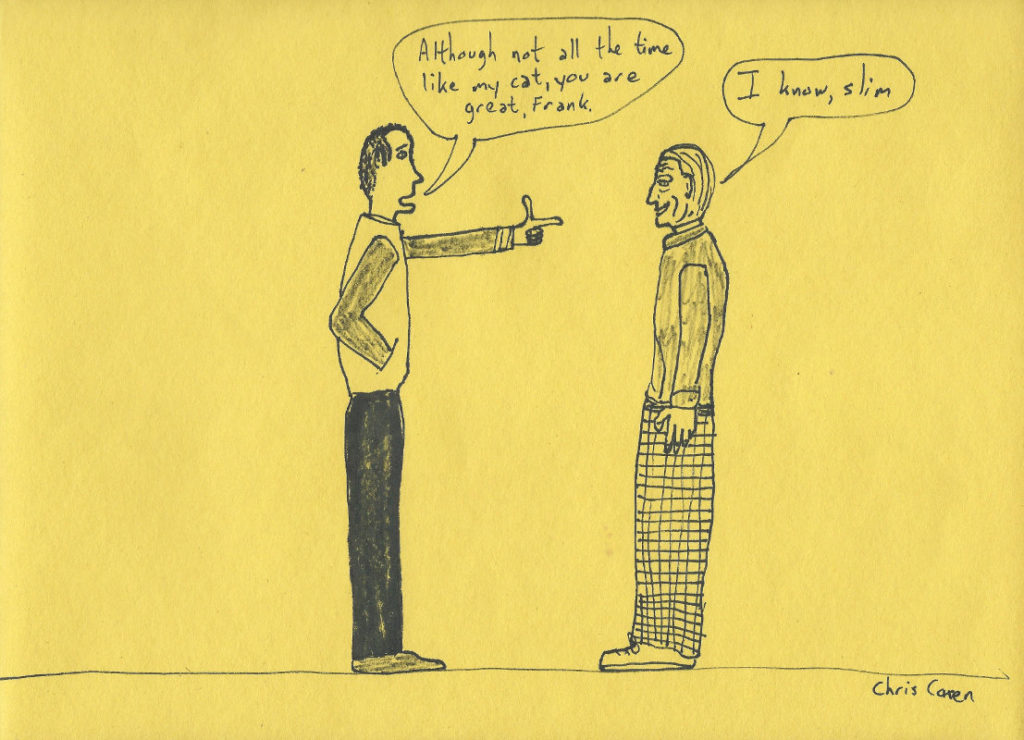

It was clear to me that Frank was great. I could see how the two of them got on so well and inspired each other to excel. Both had that classy, balanced zest for life that seemed to be passing with their generation. I don’t think either one had an irremovable passion for fuel injection. It happened to be the thing on the table at the time. It made sense to two men that not only had the natural talent needed to pull off what they pulled off, they had that ethereal thing that few have that allowed them to be certain their idea was one that would work.

I was so happy to have met Frank. He provided more insight into Mr. Pemberton than some secret diary. Although Frank exercised award-winning candor when discussing him, he was less open in matters concerning the war.

“The war changed TAP. It changed us all but it had an effect on him that was more than most.”

I didn’t dare ask Frank to expand on his statement. His demeanor changed when he brought up the war that I felt it best to leave it. At one point, I thought Frank was going to cry but no tears came out. I’ve seen this in old people sometimes. Maybe it’s just that their tear ducts are old and don’t function like they used to or maybe it’s that we all have so many tears to cry and when we use them up, that’s the end of crying for us. Either way, it looked like his eyes were dry heaving so I comforted him by covering the next round. Frank was touched.

“Chris. What I’m going to tell you now is something that will be hard for you to believe. It’s funny, Frank and I were always on the same page about people. After talking with you for the past 30 minutes, I can already tell that TAP couldn’t have made a finer choice.”

All I could do was be silent.

“TAP wanted you to have the house when he passed.”

I was made weak with this statement, like I hadn’t eaten in a few days. Part of me was unsurprised but such a monumental act of generosity such as this could never feel expected in any way. It was at this moment, literally, that my life warped through some kind of portal and into a very different destination. Frank laid out Mr. Pemberton’s desire for me to not just take over the house but to initiate the Jambassadors. As I look back, the house was the far smaller gift Mr. Pemberton gave me. The real gift, the one that evaded me to this point, the one I could never seem to locate on my own, was a higher purpose in life. I almost said “a career” which is true in a way but I would soon be enjoying that rare fortune of having my career be part of my higher purpose.

Frank invited me to his office the following Monday to meet with a lawyer or two so we could make everything official. I tried to say something to Frank as I shook his hand but I cried briefly. It’s not often that within the first 30 minutes of meeting someone for the very first time that you say goodbye in tears. But this was an encounter that could not be compared to any other I have ever known.

I left the Corrib at the same moment that the German couple was leaving. They had just finished having what looked to be an intense talk with Frank that ended with Frank entering something into a small date book. I held the door open for them, allowing them to step into a damp, raw atmosphere that had defined the entire day’s weather. The lady said “thank you” and the man said “danke” but shook his head and quickly corrected himself and said “thank you”.

“It’s okay, ‘danke’ works too.” I said.

The two smiled and the man replied, “Yes but it does not feel right to say ‘danke’ coming out of an Irish pub.”

“I can see that. My name is Chris. I was Mr. Pemberton’s handyman and friend.”

“Ahh, Thomas has mentioned you! I am Elsa and this is my husband Wolf.” Elsa spoke with what was, I believe, her first feeling of excitement in a few days.

We shook hands. “I’m Chris and it seems like everyone knows me but I don’t know anybody. I guess this is as close as I’ll get to being a celebrity.”

“Thomas told me very much about your great work and your great character.” Elsa’s English was good but I could see her translating in her mind. If she had more of a mastery of the language, she might have expressed herself with more words. But this is why I like to listen to those who speak English as a second language. They speak less and often in a more direct, honest way. Having access to too many words seems to encumber the transmission of truth.

“Thank you. I felt the same way about Mr. Pemberton. How did you know him?” After I asked this question, I immediately wished I could somehow have withdrawn it and erased it from the past. Her reaction made me realize why Elsa and Wolf kept to themselves for most of the day or kept their conversations with others brief. She was trying to summon the strength and composure to answer this question with a certain degree of truth. Wolf looked at her with caring eyes.

“Well…I have known Thomas…for a long time. I met him during the war…” Elsa could no longer contain her emotion and started to cry. I observed that her sorrow extended beyond the events of the past week. “I’m sorry…”

Wolf put his arm around her and spoke softly to her in German. He turned to me and spoke. “I am sorry. I think it is best that we go now.”

“Of course. Nice to meet you.” I waved good bye to them both and Wolf politely nodded. I lingered awkwardly there in front of the bar. My car was parked in the direction they were going and I wanted to make sure they were well on their way before I headed out. Two people that were not part of the funeral exited the bar. They looked at me quizzically since we live in a time where if you’re standing outside of a building, you must be either smoking or looking at your phone. I was doing neither and it created the mildest sensations of nervousness in them. They even looked around me to see if perhaps I was waiting for someone, an ancient and barely acceptable form of public idleness.